Influential Thinkers

The ideas of The Working Centre have evolved from the practical day to day work of the Centre while listening and integrating the ideas of social and practical visionaries of the last one hundred years. The summary biographies below use internet sources and commentary from The Working Centre to describe how these influential thinkers have had a lasting impact on The Working Centre.

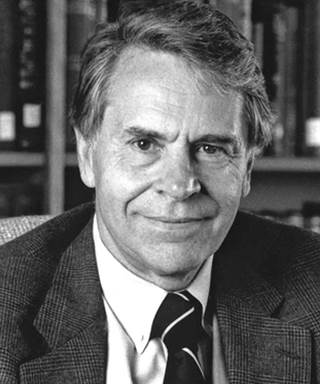

Christopher Lasch

Christopher Lasch was a public philosopher who critiqued progress from the perspective of history and democracy. He wondered what will happen when neighbourhoods, families, churches and an array of self-governing institutions – the infrastructure that teaches civic virtue – gives way to bureaucratic experiments. The study of history has often brought forth new insights into the modern world and human society. Lasch is one such historian who has taken the lessons of history and applied them to 20th century America. Through critical social analysis, Lasch describes the world as being dominated by self-absorbtion and deep class divisions. In “The Revolt of the Elites and The Betrayal of Democracy”, Lasch accuses the upper class of using its intellectual and financial resources for its own gain instead of the betterment of the nation.

“The True and Only Heaven” is a critical reflection on “progress” and a reflection on Lasch’s strong belief in traditional family values. He writes that degradation of the family unit in western culture is at the root of many societal issues, and that the weakening of the family allows other powers to influence individuals to a greater degree. Lasch has observed “In the history of civilization . . . vindictive gods give way to gods who show mercy as kill and uphold the morality of loving your enemy. Such a morality has never achieved anything like general popularity, but it lives on, even in our own enlightened age, as a reminder both of our fallen state and of our surprising capacity for gratitude, remorse, and forgiveness, by means of which we now and then transcend it.”

Dorothy Day & The Catholic Worker Movement

The Catholic Worker Movement began simply enough on May 1, 1933, when a journalist named Dorothy Day and a philosopher named Peter Maurin teamed up to publish and distribute a newspaper called “The Catholic Worker.” This radical paper promoted the biblical promise of justice and mercy. Grounded in a firm belief in the God-given dignity of every human person, their movement was committed to nonviolence, voluntary poverty, and the Works of Mercy as a way of life. It wasn’t long before Dorothy and Peter were putting their beliefs into action, opening a “house of hospitality” where the homeless, the hungry, and the forsaken would always be welcome.

Peter Maurin described the basic program of the Catholic Worker Movement as having three main components:

• Roundtable discussions for the clarification of thought

• Houses of hospitality to practice the works of mercy

• Farming communes to develop community-based production of essential goods

Over many decades the movement has protested injustice, war, and violence of all forms. Today there are some 130 Catholic Worker communities in the US and Canada. Many of the Working Centre’s ideas are rooted in Maurin and Day’s vision of “building a new society in the shell of the old,… where it is easier for people to be good”.

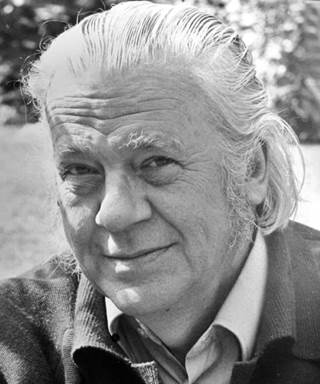

E.F. Schumacher

“Small is Beautiful” is a phrase that defines E. F. Schumacher’s work, and describes the study and action dedicated to alternative ways of looking at the economy. The Working Centre has often incorporated Schumacher’s observations into its own operations, recognizing that while large organizations and institutions dominate the social and economic landscape, it is the actions of individuals and small autonomous groups who have the flexibility and innovation needed to respond to the challenges facing each community.

The Working Centre has derived from Schumacher’s writings the three purposes of human work. What he calls Good Work:

1. First, to provide necessary and useful goods and services.

2. Second, to enable every one of us to use and thereby perfect our gifts like good stewards.

3. Third, to do so in service to, and in cooperation with, others, so as to liberate ourselves from our inborn egocentricity.

Few economists of the last fifty years have offered more striking alternatives to mainstream economic thinking than Ernest Friedrich Schumacher. Born in Germany but spending the bulk of his working life in England, Schumacher’s career afforded him the ability to critique the economic system from within, and propose alternatives – not primarily through policy prescriptions, but through a radically different attitude towards life. He spent twenty years as the Chief Economic Advisor to the National Coal Board of Britain, and through that organization became intimately acquainted with problems of energy supply and environmental sustainability. Meanwhile, his interest in gardening, his study of Buddhist and Taoist thought, and his admiration for the work and philosophy of Gandhi led him to expand his economic thinking towards a wider set of values that he called “meta-economic.”

Ivan Illich

Ivan Illich (1926 – 2002) became prominent in the 1970s with a series of brilliant, short, polemical, books on the major institutions of the industrialized world. They explored the functioning and impact of ‘education’ systems (Deschooling Society), technological development (Tools for Conviviality), energy, transport and economic development (Energy and Equity), medicine (Medical Nemesis), and work (The Right to Useful Unemployment and its Professional Enemies; and Shadow Work). Ivan Illich’s lasting contribution was a dissection of these institutions and a demonstration of their corruption and counterproductivity. Institutions like schooling and medicine had a tendency to end up working in ways that reversed their original purpose. However, his work was the subject of attack from both the left and right. In the case of the former, for example, his critique of the disabling effect of many of the institutions of welfare state was deeply problematic. However, Disabling Professions is a book all professionals should read to understand their “seamy” side, as Illich called it.

The writings and ideas contained in “Tools for Conviviality” are at the heart of many Working Centre projects. We ask the questions that Illich asked, “How can tools liberate us and serve others while providing daily subsistence?” Illich’s answer was to challenge groups and individuals to develop their own philosophy of tools by reflecting on how a humble tool like a shovel can help us heal our alienation to the world. The Working Centre interpreted this approach into the projects that we call “community tools”.

Jane Addams & Hull House

Jane Addams, born in 1860, was a member of the first generation of privileged, American women who obtained college educations and then dedicated their lives to community service and social justice. Ms. Addams was influenced by the abolitionist movement, the westward expansion of the US government, the industrial revolution, the progressive era of political reform, the Protestant ethic of hard work, and the duty to serve others. Addams attended college and graduated believing that she had been educated to serve, but she wanted to serve in a way that would have a real impact on the lives of people who had not had the same advantages as she. Addams saw an opportunity to improve the lives of the poor by creating a community of people who lived and worked together to provide for the needs of that community of which she was an equal participating member. This community began with Hull House, a place where the underprivileged would no longer have to feel like second-class citizens, and where the social ills of the urban ‘ghetto’ could be fought at a grassroots level. Jane Addams “aimed to create citizens, not manage clients”; this thinking is important to the Working Centre in its goal of helping people find honest and fulfilling work.

Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs has helped us see how revitalization is an ecological process that is as diverse as the rainforest and has the possibility of creating new work from what has been discarded. In the September 2000 Good Work News, the article “Why Sharing in Common is Like Forest Ecology” describes the relevance of Jacob’s theories at The Working Centre.

“Jacobs uses the example of a desert or a forest. Each could exist where the other had been. Deserts are barren because the sunlight has only sand and rocks to filter through. “The passage of energy is swift, simple and vanishing, leaving no evidence of the passage.”

“A forest ecosystem is completely different. It grows and expands because of the sun’s energy flowing through diverse and roundabout ways through zillions of organisms. “Once sunlight is captured in the conduit, it’s not only converted but repeatedly reconverted, combined and recombined, cycled and recycled, as energy/matter is passed from organism to organism.” A forest teems with species while a desert is comparatively barren. But if the same forest is clear-cut and the soil allowed to bake, soon you will have a desert.

“Biology’s recent understanding of this phenomenon of multiple recombinations of energy passage has much to offer for understanding the way communities grow. Creative ideas are best supported by an environment where other diverse, decentralized activities are taking place. Energy needs to be co-operatively and not so co-operatively passed back and forth through numerous interdependent links. Over the years, The Working Centre has developed a small supporting web of initiatives that support people in important ways by providing access to tools, projects and other supports.”

Jane Butzner Jacobs (born 1916) was a writer, activist, and city aficionado. She was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania and moved to Toronto Ontario in 1968 where she lived until she passed away in April 2006. Jacobs spent her life since studying the nature of cities and urban life, and has published several influential works including “Death and Life of Great American Cities” (1961) and “Systems of Survival” (1992). Jacobs’ philosophies centre on the idea that modern city planning is counterproductive to economic prosperity and is detrimental to the way in which people live in urban areas.

Jim Lotz

Since 1960, Jim Lotz had carried out research and been active on the problems of unemployed youth, urban development, squatters, new towns, declining communities, cross-cultural education, bookselling in Canada, and the social, human and community impact of development in Canada, Scotland and Alaska.

He is the author of Northern Realities (1970), and co-author of Cape Breton Island (1974). He serves in an editorial capacity with Plan Canada, Science Forum, Canadian Review and Axiom. A former federal civil servant and university professor, he now lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, earning a living as an independent research worker, freelance writer, organizer and teacher.

Lotz is the author of Understanding Canada, which traces the concept of community development from its beginnings in colonial Africa to recent attempts at self help in Canada, and relates it to the ideas of individualism and liberalism. Focusing especially on the Atlantic Provinces, Lotz looked at efforts to ‘help” the poor from the top down and from the bottom up. He analyzed the successes of the approach of the Antigonish Movement which flourished in the Thirties. Lotz suggested models, goals and roles in community development indicate that we can meet rapid change in a positive and creative way.

Ken Westhues

In the mid 1980’s, as The Working Centre was experimenting with new ways of doing community work, we were very fortunate to find the support of Ken Westhues as a board member and mentor. As a well published sociologist at the University of Waterloo he was committed to a conception of sociology that grew out of “intimate, democratic engagement in practical affairs”. Westhues showed us that “the early practitioners [of sociology] were not, in the main, professors sequestered in academia but public men and public women, activist intellectuals whose books were intended to reshape for the better the theaters of conflict and politics out of which they were written.” Westhues offered The Working Centre a continuing “interplay between disciplined, empirical social thought and social action.”

Building Relationships Where People Are Real, an essay by Westhues in the late 1980’s became a description of how The Working Centre described its informal, community building approach. In the first version of that essay, Westhues describes increased scale, the concentration of capital and the resulting decrease in ownership of property, the increased scale of organizations, the bureaucratization of organizations and the professionalization of services as the main social problems. In short, our culture’s organization of work was guaranteed to alienate workers, decrease creativity and minimize craft and workmanship.

Shaping, influencing and describing alternatives to the bureaucratic status quo have been Ken’s main role at The Working Centre. Below are some examples of how social thought interplays with social action and how democratic thought is developed through practical action.

“…as a place that counters our bureaucratized world. We seek to give people the dignity and respect they deserve, to help people take charge of their own lives, to enable us all to escape the doldrums of consumerism and find our way to the joy of producing for ourselves.”

“In the way it has pursued its educational mission, the Working Centre has also fostered distinct and invaluable social skills: how to teach, learn, and live in a respectful, reciprocal, democratic way. Hierarchical, top-down models of schoolwork, as of work in general, are avoided here in favour of more egalitarian models. Quality, productivity, job satisfaction, friendship and joy are achieved through mutual aid. Teachers and learners take turns talking and listening, showing one another how to do new things.”

“Against the ethic of mass consumerism, The Working Centre pits the ethics of producerism drawn from thinkers like Schumacher, Illich and Lasch. It means acquiring skills and seizing opportunities to produce more necessities and luxuries of life on one’s own or in small groups. Unemployment from this perspective need not mean deprivation, the loss of the good life, but a chance to redefine the good life in a more genuine, joyful and sustainable way, more in terms of producing power than of purchasing power.”

“This part of Ontario was not founded by imperial edict. Our community arose from the grassroots efforts of settlers finding their own way along the trail of the black walnut trees. The defining character of Waterloo Region is as a place of decentralized power, a place where ordinary people make history, free of despotism of any kind. The Waterloo School of Community Development is rooted in these local, democratic traditions. It aims to maintain and deepen those traditions in the large, urban, diverse, high-tech setting the Region has become.”

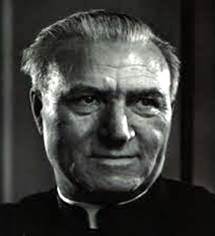

Moses Coady and the Antigonish Movement

Moses Coady is a unique Canadian example for his work creating a social movement that combined adult education with support for disadvantaged workers. The Antigonish Movement evolved from the pioneering work of Rev. Dr. Moses Coady and Rev.Jimmy Tompkins in the 1920s. The local community development movement originated as a response to the poverty afflicting farmers, fishers, miners, and other disadvantaged groups in Eastern Canada. Dr. Coady and his associates used a practical and successful strategy of adult education and group action that began with the immediate economic needs of the local people.

The philosophic principles of the Antigonish Movement were well established as guidelines for the work of the Movement beginning in the 1930s. However, it was a decade later that they were articulated. The Antigonish Movement emphasized respect for the individual and belief that a participatory group process based on adult education and socioeconomic cooperation is the most effective and beneficial means to affect social change for the better.

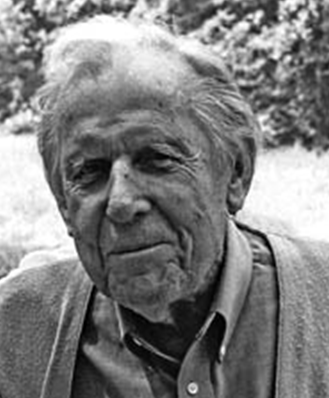

Thomas Berry

Thomas Berry provides a spiritual guide to the environment. In his most recent book, The Great Work, he describes how, “such deterioration results from the rejection of the inherent limitations of human existence and from an effort to alter the natural functioning of the planet in favour of a humanly constructed wonderworld.” The optimistic subtitle of this book is Our Way into the Future. Berry seeks to change our learned destructive behaviour by supporting “efforts towards living creatively within the organic functioning of the natural world. Earth as a biospiritual planet must become for us the basic referent in identifying our own future.”

In Dream of the Earth, Berry weaves together culture, consciousness and ecology to give the reader a flowing account of how we have allowed our culture of consumption to dominate the natural world. Berry is at his strongest when he describes where this is taking us:

“We have violated the rivers by making them toxic. We have violated the air by poisoning it. We have violated the sea by overfishing and by making it a dumping ground. The list goes on and includes the clear-cutting of trees that in the long run will make the Earth uninhabitable.”

Berry wants us to evolve our conscience and ecology to recognize that God’s creation will be incapable of supporting life unless we develop a higher sense of the sacred. “There must be a mystique of rain…the same is true about soil, the trees, forests and other natural phenomena.” Berry calls for a new religious sensitivity or else we are in danger of plundering the very foundations of life itself.

Thomas Berry is a historian of cultures and a writer with special concern for the foundation of cultures in their relations with the natural world. He comes from the hill country of North Carolina where he was born in 1914. He entered a monastery in 1934 and earned his doctoral degree in western intellectual history. Through his writings, Berry conveys the message that all life exists both individually, and as part of a universal whole in which all things are intrinsically linked. He sees modern man seeking to gain ever-tighter control over his environment, upsetting the natural balance. In creating tightly controlled environments, mankind detracts from its own creative capacity as well, and adds to the workload required to maintain society. Berry also reminds us that there are many lessons to be learned from history, and that they must not be forgotten.

Wendell Berry

Wendell Berry has written extensively on the moral significance of local work and how it builds community. Poet, essayist, farmer, and novelist Wendell Berry was born on August 5, 1934, in Newcastle, Kentucky. He attended the University of Kentucky at Lexington where he received a B.A. in English in 1956 and an M.A. in 1957. Berry is the author of more than thirty books of poetry, essays, and novels. Some of his more influential works include “Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community” (1994), “The Unsettling of America : Culture & Agriculture” (1996), “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” (1987), “What Are People For?” (1990) and “Home Economics”.

In his writings, Berry describes means by which people can ‘get back to their roots’, and stresses the importance of effectively run agricultural communities in which the needs of all people are considered and cared for by the community. At the same time he analyses concisely why our culture is moving in a different direction, “We have made a social ideal of minimal involvement in the growing and cooking of food.” The community unit is considered by Berry to be the base level of economic organization; “A community economy is not an economy in which well-placed persons can make a ‘killing’. It is an economy whose aim is generosity and a well-distributed and safeguarded abundance”